Our Immune System - important and effective

Body's own defence for a long and healthy life

In the course of my voluntary work I am repeatedly asked what the functions and effects of our immune system are and how it can or should be strengthened.

What significance do immunotherapies have and are they meaningful?

The topic “Immune system” is one of many which, like so many others, although not directly connected to my responsibilities, comes up time and again because the group participants find it interesting. Since the immune system is a very versatile and complicated system I’ve decided to split this article up into different parts and so, this is the first part you’re reading now.

The immune system is very complex, a large number of cells and proteins are busy warding off pathogens like for example bacteria, viruses, fungi, parasites or other exogenous substances and to generally monitor all processes in the body. The only guarantee for a long and healthy life is a well-functioning body defence system.

Our body has an immune system which is one of the largest and heaviest organs in our body – it weighs around 2 kg in an adult. However, it is not located in one specific place in our bodies, but rather divided up between blood, lymph system, tissues, organs and skin.

White blood cells are produced in the bone marrow. The thymus gland, the spleen, tonsils and the colon are places where the defence cells are prepared for their work. The lymph nodes are like checkpoints and are places where bacteria is destroyed.

The immune system is formed in the mother’s womb. As soon as a baby is born, the immune system comes into contact with pathogens. The mother's blood initially protects the baby, but its own defence is already developed.

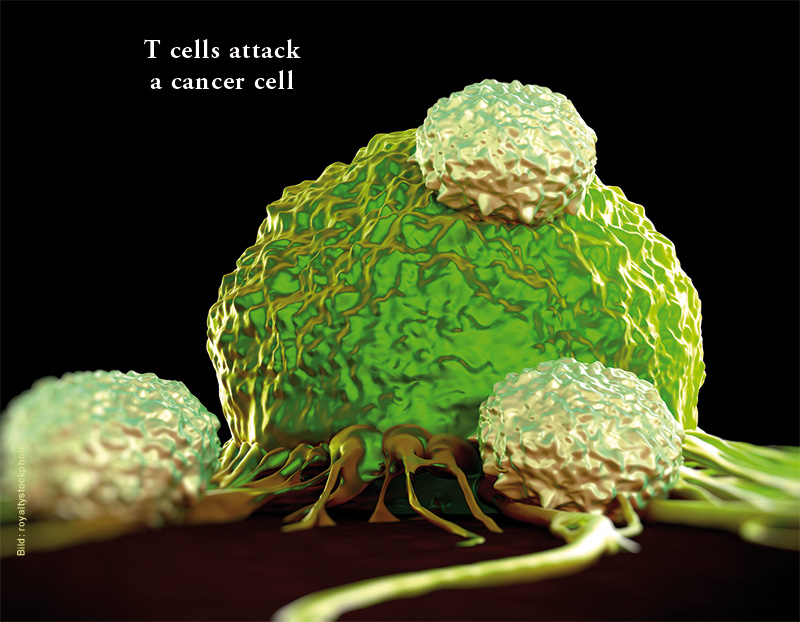

In our body millions of different endogenous antibodies (proteins) make different pathogens visible for the immune defence. Special immune cells (the so-called T-cells) are the watchmen. They recognise the foreign, dangerous intruders and organise the actual defensive action together with other elements of the immune system. So-called killer cells and scavenger cells get rid of the pathogenic microbes in the end.

A new-born baby would not be able to live longer than a few days without an immune system. Microorganisms invade the body through every bodily orifice as well as while breathing, eating and drinking and through every scratch in the skin. Many microorganisms are harmless, some even help their human hosts with digestion, but some would kill the body which gives them nourishment and living space in their quest to reproduce rapidly.

We owe a lot to our immune system, without it a simple cough would kill us. We can eat, for instance, salad, yoghurt and meat without becoming ill. We often survive injuries, which inevitably occur in the course of a lifetime, unscathed.

No system is perfect, and fatal mistakes can happen which can wreak havoc. For example, the immune system sometimes attacks its own body tissue and so an autoimmune disorder develops with the formation of antibodies against own body parts. Familiar forms are e.g. rheumatism (joints), multiple sclerosis (nerves) or diabetes (islet cells) and also the autoimmune form of pancreatic inflammation.

We don’t yet know today all the things that the immune system does and so we are always being supplied with new and interesting research discoveries, which lead to new medical therapies (immunotherapy).

Whether an illness breaks out or which course it takes depends on the performance of the immune system. Many processes are constantly taking place in the body, of which we hardly notice anything if our immune system is intact. If, however, the immunological barrier is not functioning properly or is perhaps even damaged, we become ill. That happens if our immune system has been weakened by illness, for example flu, medicines or other influences, or if pathogens are stronger and reproduce swiftly.

Our immune system also recognises and attacks cancer cells but still some cancer cells manage to outsmart the defence mechanism or even slip past it completely, which can lead to the outbreak of cancer.

The human body has developed a whole row of defence factors which puts it in the position of being able to repulse pathogens like, for example:

- Skin and mucous membranes which serve as protective barriers

- Many enzymes in saliva, sweat, tears or the acid in the stomach kill the invading pathogens

- And the flushing out of the urinary organs has a similar effect

Should hospital pathogens manage to invade our immune system, then a well-functioning immune system protects us from falling ill. It’s important that it recognises them as “foreign” i.e. not belonging to its own body and destroys them.

The immune system learns from birth on what is “foreign” and doesn’t belong to the body. Substances which some into contact with our bodies from outside during our lives, are recognised as being “foreign”.

Inflammatory reactions such as increased blood circulation (redness), pain, swelling, and excess heat can be the result, as well as a high temperature. We call these reactions an immune response.

Important components of our immune system

Leuckocytes (white blood cells) are the immune system’s cells and are produced in the bone marrow. They are “trained” in lymphatic tissue, which consists of: lymph nodes, the spleen, the thymus gland and the tonsils. They circulate in the blood or wander into the tissues, where they perform a sort of watchdog function. There are different subspecies of leukocytes.

Granulocytes make the front line of defence against bacteria cells and are the most common kind of white blood cells. They are capable of leaving the blood vessels and wandering into tissue to help fight against inflammation and eliminate parasites and pathogens.

Lymphocytes play an important part in the acquired specific defence. They can be divided into two groups, the T- and the B-lymphocytes.

B-lymphocytes are mostly to be found in the spleen and the lymph nodes. They are important for the production of specific antibodies which recognise foreign structures. These are often responsible for the development of allergies and autoimmune diseases (an improper function of the body).

T-lymphocytes (T-cells) are, above all, responsible for the organisation of the defence. They send messages through messenger substances to scavenger cells (phagocytes), B-lymphocytes and other cells involved in the immune defence. T-cells are stimulated to become active. They are divided into different sub-groups according to their tasks and functions: T-helper-cells, T-Suppressor cells and (cytotoxic) T-Killer-cells, these are also responsible for cancer defence and used in immunotherapy. Alongside Granulocytes and Lymphocytes there are also Monocytes.

Monocytes are large cells which develop into macrophages when they leave the blood vessels and move into the tissues. Granulocytes and monocytes are capable of absorbing bacteria and other micro-organisms, cell debris and other particles and then later to save or dissolve them. These cells are called Phagocytes or scavenger cells.

Two systems – one job

Our immune system is in two parts: the congenital general, so-called non-specific and the acquired, specialized, so-called adaptive defence. Each system has a certain function and they work closely together. Each system has a large number of immune responses of the cells and the protein molecules involved, which fulfil special tasks.

The Congenital Immune System

The Congenital Immune System is the non-specific defence system and the first shield in our body. Granulocytes and macrophages are part of the congenital system. It is supported through germicidal tissue substances, so-called antimicrobial peptides or cleaving enzymes (e.g. in saliva). This part of our immune system accompanies us from birth on and disposes of 90% of all defence tasks. However, it works with a limited choice of recognition patterns for foreign organisms and cannot adapt to new or recurrent situations. The acquired immune system takes care of these gaps.

The Acquired Immune System

The Acquired Immune System has a tailor-made and well-directed defence for each possible foreign body and for each newly acquired pathogen. The specialised lymphocytes play an important part thereby. The body has a huge collection of lymphocytes with differing surface structures. They recognise the structures of intruders (so-called antigens), so that there are always some lymphocytes which fit the foreign substances and can be activated if necessary. Apart from that, antibodies suitable for each pathogen are produced for acceleration or elimination.

There are lymphocytes which are like the memory of the immune system (so-called dendritic cells). They have a life-long memory of certain antigens once they have had contact with them. If there is contact with the pathogens again, they'll take immediate defensive action.

Katharina Stang and Mechthild Maiß

Sources:

www.allergieinformationsdienst.de

Book „Krieg in unserem Körper“ from Gabriele Kautzmann